I don't have a game of the year. In the same way that multiple games left profound and lasting influences on me in 2011, several have likewise done so in 2012--Journey, Mass Effect 3, and The Walking Dead among them.

So instead of writing any kind of GOTY post, I will instead direct readers to Sparky Clarkson's The Year of the Games roundup, a collection to which I and nearly a dozen of my colleagues and peers contributed. It's been a fascinating year, as the big-budget, AAA games wrap up franchises and stall out, waiting on a new console generation, and as indie and avant-garde-inspired gaming well and truly comes into its own.

Likewise, Critical Distance has once again rounded up their must-read highlights of the year, and they are indeed pieces that should be read.

And as for me? Well. I had many, many beginnings in 2012, and some endings too. I look forward to seeing what games inspire me to write too much in 2013.

Monday, December 31, 2012

Saturday, December 29, 2012

The Surprising Moral Clarity of Mass Effect 3

I've been working on a commissioned feature about film noir lighting in video games. Without going into what I'm writing in that essay, my very first thought was: "Oh, that's easy. I've played Mass Effect 2."

ME2 casts Shepard in an ambiguous moral position. Not only does the paragon/renegade problem carry over from the first game, but its effects are amplified dramatically. With interrupts added to the game--sudden, one-click decision points that add to Shepard's paragon or renegade scores--as well as charm and intimidate keying to reputation, rather than to skill points, the question of Shepard's soul begins to matter more.

As well, she is in a more tenuous position with regards to, well, everything. Now employed by the shadowy Illusive Man, she is working for Cerberus, known from the first game only as a terrorist organization. The crew she assembles around her is full of misfits, exiles, and murders who, if we're lucky, mostly turn out to have hearts of gold, or at least good intentions.

Of course, we all know where the road paved with good intentions leads.

The essay in question will be running in early 2013, and I have been asked to make it current, to tie it to one or more big 2012 releases. Knowing how strongly Mass Effect 2 relies on the conventions of film noir and neo-noir, I thought that my sprawling, ludicrous collection (1800+) of Mass Effect 3 screenshots would lend me the perfect inspiration.

I was wrong.

|

| It's Blade Runner! It's Double Indemnity! No, wait: it's Thane! |

ME2 casts Shepard in an ambiguous moral position. Not only does the paragon/renegade problem carry over from the first game, but its effects are amplified dramatically. With interrupts added to the game--sudden, one-click decision points that add to Shepard's paragon or renegade scores--as well as charm and intimidate keying to reputation, rather than to skill points, the question of Shepard's soul begins to matter more.

As well, she is in a more tenuous position with regards to, well, everything. Now employed by the shadowy Illusive Man, she is working for Cerberus, known from the first game only as a terrorist organization. The crew she assembles around her is full of misfits, exiles, and murders who, if we're lucky, mostly turn out to have hearts of gold, or at least good intentions.

Of course, we all know where the road paved with good intentions leads.

The essay in question will be running in early 2013, and I have been asked to make it current, to tie it to one or more big 2012 releases. Knowing how strongly Mass Effect 2 relies on the conventions of film noir and neo-noir, I thought that my sprawling, ludicrous collection (1800+) of Mass Effect 3 screenshots would lend me the perfect inspiration.

I was wrong.

With only a handful of exceptions (as in the shuttle, above), Shepard's lighting in Mass Effect 3 is surprisingly clear and unambiguous. Even when she is in a visually dark location, the lighting spares her. Shadows fall around her, but not on her; even her companions are largely of the light.

As the game itself gets darker, in every possible sense of the word, the ambiguity becomes stripped away from the Normandy and its passengers just as it becomes stripped away from the plot. Yes, every decision has consequences, and the strings of three games' worth of choices bear out in many meaningful ways. But even while that matters, the time for ambiguity is, simply, behind Shepard and behind us.

By ME3, the reapers are here. They are destroying worlds, cultures, civilizations, life... everything. There is no question of "sides," of "morality." Respect her (paragon) or fear her (renegade), Shepard is our hero and the hero's time is now.

In fact, the more I browse my enormous gallery of images, the more I feel like Mass Effect 3 is lit with a series of spotlights. Where Mass Effect 2 threw diagonal shadows around the place to create effect, ME3 is doing everything it can with framing, light, and color to highlight our heroes, fighting to the end in a darkened world.

|

| Sometimes that world is darkened a little too literally. |

Indeed, even in an area and on a mission where moral ambiguity and character confusion could easily have been added, the game avoids that construction. I am speaking of a point somewhere near the end of Act 2 (relatively speaking) where the asari Council representative has summoned Shepard, to impart a secret and necessary piece of information.

The asari's motives and goals are unclear. She could be honest; she could be dishonest. Shepard's reaction is unclear: the player can be angry or resigned. The conversation takes place in an office, where light and posing could easily have conveyed ambiguity and confusion. Instead, the conversation is brightly lit, with all the whites the Citadel presidium has to offer. The greatest distance the scene ever creates comes through framing one shot on the other side of a window, hinting at a sense of voyeurism and eavesdropping.

|

| You know, if you had mentioned this BEFORE your planet was invaded, that would have been helpful. |

By the time the Shepard's saga reaches its third and final game, that which is... well, is. Most of the questions and mysteries are removed from the story, and the moral ambiguity of our players along with. This is not a game for introducing new characters, or questioning their motives; this is a time to revisit the consequences of the stories we already told, and resolving the fates of characters we already know.

Even knowing that, though, I was surprised at how strongly the visuals bear that out. Subconsciously, they of course reinforced that message the entire time I was playing. That's what visual language does.

There is also, of course, an exception. Or in fact, a pair of exceptions. The Leviathan and Omega DLC add-ons each provide dozens of examples of moral ambiguity and character confusion conveyed through noir-like use of light and shadow. And it makes sense: these are the segments of game that introduce new characters and new concepts that stand slightly to the side of the hero's straightforward quest for war resources. Aria, Nyreen, and even the Leviathan itself are all moral wildcards when they are introduced, standing aside from Shepard's binary perspective, and so the lighting lets us stand in Shepard's shoes for a little while, uncertain about who we have just met.

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

In which I develop an opinion on Capcom

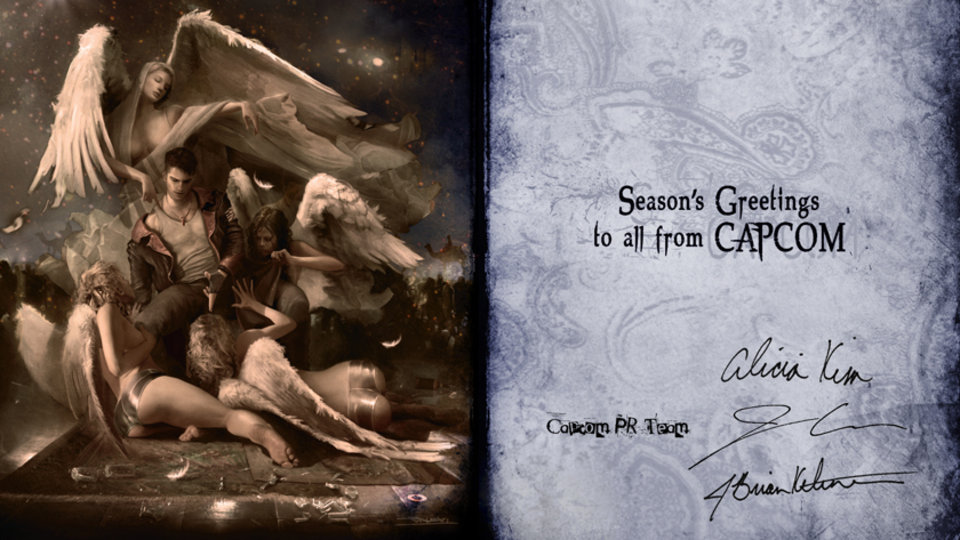

I really had no particularly strong feelings on either Capcom or on their upcoming Devil May Cry game until today.

But then, via Samit Sarkar, there was this.

That, right there, is the Christmas card that Capcom PR sent out this year.

Not only is Dante--that charming fellow on the left, there--surrounded by angels, but the angels are, of course:

Wow.

I didn't care about Capcom until now. But as of today, they're on my personal shit list--there to remain, I suspect, more or less permanently.

Well done, Capcom PR!

But then, via Samit Sarkar, there was this.

That, right there, is the Christmas card that Capcom PR sent out this year.

Not only is Dante--that charming fellow on the left, there--surrounded by angels, but the angels are, of course:

- women

- light-skinned women

- big-busted light-skinned women

- big-busted light-skinned women with hourglass figures

- big-busted light-skinned women with hourglass figures and prodigious, posed posteriors

Wow.

I didn't care about Capcom until now. But as of today, they're on my personal shit list--there to remain, I suspect, more or less permanently.

Well done, Capcom PR!

Monday, December 3, 2012

Music

Back in the summer of 2011, Kill Screen was taking pitches for pieces for their sound issue. I sent one in; Chris Dahlen, the editor-in-chief, accepted it.

It was the first piece I ever sold. "Giddy" doesn't even begin to describe how happy I was. I had enormous respect for the magazine and couldn't believe I'd get to be among the all-star list of contributors on that front page.

Alas, the piece got cut for space, and although Chris originally planned for it to fit into the following issue, he left Kill Screen and the new editors chose to take subsequent issues in a new direction. My piece no longer fit.

I showed it to Kirk Hamilton, the Melodic block editor, when I first came to Kotaku, and we agreed that it was great and that we should do the hard work of editing it to fit, sometime, but (more due to me than to him), "sometime" never managed to come before my time at the site ran out.

So.

It's not perfect, and it could use an editor, but here's that piece, in its entirety. Because sometimes, you just need your music to make you a goddamn space marine.

It was the first piece I ever sold. "Giddy" doesn't even begin to describe how happy I was. I had enormous respect for the magazine and couldn't believe I'd get to be among the all-star list of contributors on that front page.

Alas, the piece got cut for space, and although Chris originally planned for it to fit into the following issue, he left Kill Screen and the new editors chose to take subsequent issues in a new direction. My piece no longer fit.

I showed it to Kirk Hamilton, the Melodic block editor, when I first came to Kotaku, and we agreed that it was great and that we should do the hard work of editing it to fit, sometime, but (more due to me than to him), "sometime" never managed to come before my time at the site ran out.

So.

It's not perfect, and it could use an editor, but here's that piece, in its entirety. Because sometimes, you just need your music to make you a goddamn space marine.

Sunday, December 2, 2012

Go read this

File under, "I really wish I had written this:" Katherine Cross's "Game Changer."

Cross does her homework and her research, and articulates very clearly and cleanly the theories that I--and anyone else who examines sexism in gaming--have bandied about for ages. She even looks at the moving goalposts: if women like it, it is no longer a "real game."

It is hardly surprising that some men perceive the gaming world as, in Kimmel’s words, a “virtual men’s locker room” threatened by the presence of women. When women inhabit this space, claim visibility, and attempt to shape it, their presence becomes an existential threat to that “not PC” safe space that some of these young men enjoy. When abuse occurs, the conceit is that it’s “just a game,” which enables people to—in the words of one of Kimmel’s interviewees—“offend everyone!” It’s not like real life, which is too, well, real to risk flagrantly violating norms of decorum. But, at the same time, these male gamers know that the space is a real, tangible thing, in need of protection. Their “offending” serves to police the boundaries of who can and cannot inhabit gaming culture, and to keep out people who threaten “their” space.

Cross does her homework and her research, and articulates very clearly and cleanly the theories that I--and anyone else who examines sexism in gaming--have bandied about for ages. She even looks at the moving goalposts: if women like it, it is no longer a "real game."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)