I don't have a game of the year. In the same way that multiple games left profound and lasting influences on me in 2011, several have likewise done so in 2012--Journey, Mass Effect 3, and The Walking Dead among them.

So instead of writing any kind of GOTY post, I will instead direct readers to Sparky Clarkson's The Year of the Games roundup, a collection to which I and nearly a dozen of my colleagues and peers contributed. It's been a fascinating year, as the big-budget, AAA games wrap up franchises and stall out, waiting on a new console generation, and as indie and avant-garde-inspired gaming well and truly comes into its own.

Likewise, Critical Distance has once again rounded up their must-read highlights of the year, and they are indeed pieces that should be read.

And as for me? Well. I had many, many beginnings in 2012, and some endings too. I look forward to seeing what games inspire me to write too much in 2013.

Monday, December 31, 2012

Saturday, December 29, 2012

The Surprising Moral Clarity of Mass Effect 3

I've been working on a commissioned feature about film noir lighting in video games. Without going into what I'm writing in that essay, my very first thought was: "Oh, that's easy. I've played Mass Effect 2."

ME2 casts Shepard in an ambiguous moral position. Not only does the paragon/renegade problem carry over from the first game, but its effects are amplified dramatically. With interrupts added to the game--sudden, one-click decision points that add to Shepard's paragon or renegade scores--as well as charm and intimidate keying to reputation, rather than to skill points, the question of Shepard's soul begins to matter more.

As well, she is in a more tenuous position with regards to, well, everything. Now employed by the shadowy Illusive Man, she is working for Cerberus, known from the first game only as a terrorist organization. The crew she assembles around her is full of misfits, exiles, and murders who, if we're lucky, mostly turn out to have hearts of gold, or at least good intentions.

Of course, we all know where the road paved with good intentions leads.

The essay in question will be running in early 2013, and I have been asked to make it current, to tie it to one or more big 2012 releases. Knowing how strongly Mass Effect 2 relies on the conventions of film noir and neo-noir, I thought that my sprawling, ludicrous collection (1800+) of Mass Effect 3 screenshots would lend me the perfect inspiration.

I was wrong.

|

| It's Blade Runner! It's Double Indemnity! No, wait: it's Thane! |

ME2 casts Shepard in an ambiguous moral position. Not only does the paragon/renegade problem carry over from the first game, but its effects are amplified dramatically. With interrupts added to the game--sudden, one-click decision points that add to Shepard's paragon or renegade scores--as well as charm and intimidate keying to reputation, rather than to skill points, the question of Shepard's soul begins to matter more.

As well, she is in a more tenuous position with regards to, well, everything. Now employed by the shadowy Illusive Man, she is working for Cerberus, known from the first game only as a terrorist organization. The crew she assembles around her is full of misfits, exiles, and murders who, if we're lucky, mostly turn out to have hearts of gold, or at least good intentions.

Of course, we all know where the road paved with good intentions leads.

The essay in question will be running in early 2013, and I have been asked to make it current, to tie it to one or more big 2012 releases. Knowing how strongly Mass Effect 2 relies on the conventions of film noir and neo-noir, I thought that my sprawling, ludicrous collection (1800+) of Mass Effect 3 screenshots would lend me the perfect inspiration.

I was wrong.

With only a handful of exceptions (as in the shuttle, above), Shepard's lighting in Mass Effect 3 is surprisingly clear and unambiguous. Even when she is in a visually dark location, the lighting spares her. Shadows fall around her, but not on her; even her companions are largely of the light.

As the game itself gets darker, in every possible sense of the word, the ambiguity becomes stripped away from the Normandy and its passengers just as it becomes stripped away from the plot. Yes, every decision has consequences, and the strings of three games' worth of choices bear out in many meaningful ways. But even while that matters, the time for ambiguity is, simply, behind Shepard and behind us.

By ME3, the reapers are here. They are destroying worlds, cultures, civilizations, life... everything. There is no question of "sides," of "morality." Respect her (paragon) or fear her (renegade), Shepard is our hero and the hero's time is now.

In fact, the more I browse my enormous gallery of images, the more I feel like Mass Effect 3 is lit with a series of spotlights. Where Mass Effect 2 threw diagonal shadows around the place to create effect, ME3 is doing everything it can with framing, light, and color to highlight our heroes, fighting to the end in a darkened world.

|

| Sometimes that world is darkened a little too literally. |

Indeed, even in an area and on a mission where moral ambiguity and character confusion could easily have been added, the game avoids that construction. I am speaking of a point somewhere near the end of Act 2 (relatively speaking) where the asari Council representative has summoned Shepard, to impart a secret and necessary piece of information.

The asari's motives and goals are unclear. She could be honest; she could be dishonest. Shepard's reaction is unclear: the player can be angry or resigned. The conversation takes place in an office, where light and posing could easily have conveyed ambiguity and confusion. Instead, the conversation is brightly lit, with all the whites the Citadel presidium has to offer. The greatest distance the scene ever creates comes through framing one shot on the other side of a window, hinting at a sense of voyeurism and eavesdropping.

|

| You know, if you had mentioned this BEFORE your planet was invaded, that would have been helpful. |

By the time the Shepard's saga reaches its third and final game, that which is... well, is. Most of the questions and mysteries are removed from the story, and the moral ambiguity of our players along with. This is not a game for introducing new characters, or questioning their motives; this is a time to revisit the consequences of the stories we already told, and resolving the fates of characters we already know.

Even knowing that, though, I was surprised at how strongly the visuals bear that out. Subconsciously, they of course reinforced that message the entire time I was playing. That's what visual language does.

There is also, of course, an exception. Or in fact, a pair of exceptions. The Leviathan and Omega DLC add-ons each provide dozens of examples of moral ambiguity and character confusion conveyed through noir-like use of light and shadow. And it makes sense: these are the segments of game that introduce new characters and new concepts that stand slightly to the side of the hero's straightforward quest for war resources. Aria, Nyreen, and even the Leviathan itself are all moral wildcards when they are introduced, standing aside from Shepard's binary perspective, and so the lighting lets us stand in Shepard's shoes for a little while, uncertain about who we have just met.

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

In which I develop an opinion on Capcom

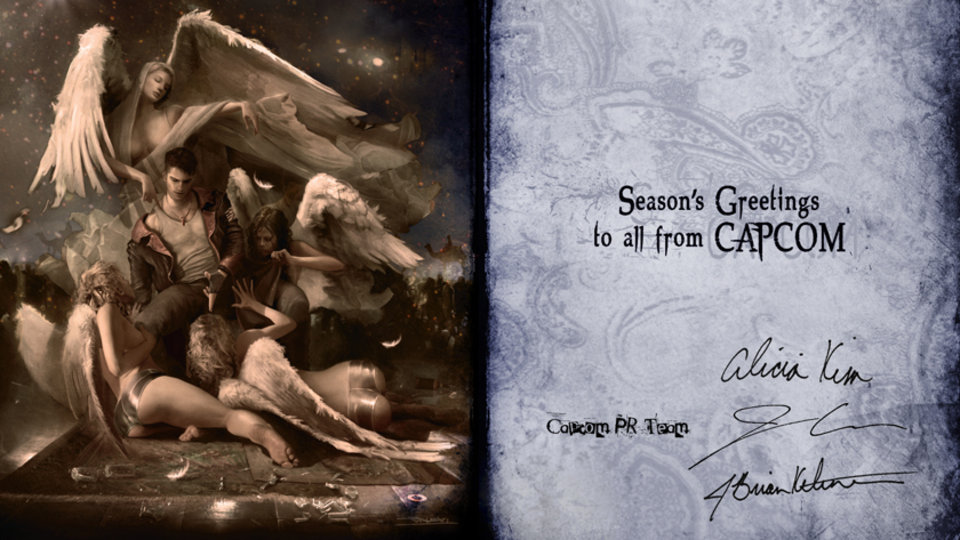

I really had no particularly strong feelings on either Capcom or on their upcoming Devil May Cry game until today.

But then, via Samit Sarkar, there was this.

That, right there, is the Christmas card that Capcom PR sent out this year.

Not only is Dante--that charming fellow on the left, there--surrounded by angels, but the angels are, of course:

Wow.

I didn't care about Capcom until now. But as of today, they're on my personal shit list--there to remain, I suspect, more or less permanently.

Well done, Capcom PR!

But then, via Samit Sarkar, there was this.

That, right there, is the Christmas card that Capcom PR sent out this year.

Not only is Dante--that charming fellow on the left, there--surrounded by angels, but the angels are, of course:

- women

- light-skinned women

- big-busted light-skinned women

- big-busted light-skinned women with hourglass figures

- big-busted light-skinned women with hourglass figures and prodigious, posed posteriors

Wow.

I didn't care about Capcom until now. But as of today, they're on my personal shit list--there to remain, I suspect, more or less permanently.

Well done, Capcom PR!

Monday, December 3, 2012

Music

Back in the summer of 2011, Kill Screen was taking pitches for pieces for their sound issue. I sent one in; Chris Dahlen, the editor-in-chief, accepted it.

It was the first piece I ever sold. "Giddy" doesn't even begin to describe how happy I was. I had enormous respect for the magazine and couldn't believe I'd get to be among the all-star list of contributors on that front page.

Alas, the piece got cut for space, and although Chris originally planned for it to fit into the following issue, he left Kill Screen and the new editors chose to take subsequent issues in a new direction. My piece no longer fit.

I showed it to Kirk Hamilton, the Melodic block editor, when I first came to Kotaku, and we agreed that it was great and that we should do the hard work of editing it to fit, sometime, but (more due to me than to him), "sometime" never managed to come before my time at the site ran out.

So.

It's not perfect, and it could use an editor, but here's that piece, in its entirety. Because sometimes, you just need your music to make you a goddamn space marine.

It was the first piece I ever sold. "Giddy" doesn't even begin to describe how happy I was. I had enormous respect for the magazine and couldn't believe I'd get to be among the all-star list of contributors on that front page.

Alas, the piece got cut for space, and although Chris originally planned for it to fit into the following issue, he left Kill Screen and the new editors chose to take subsequent issues in a new direction. My piece no longer fit.

I showed it to Kirk Hamilton, the Melodic block editor, when I first came to Kotaku, and we agreed that it was great and that we should do the hard work of editing it to fit, sometime, but (more due to me than to him), "sometime" never managed to come before my time at the site ran out.

So.

It's not perfect, and it could use an editor, but here's that piece, in its entirety. Because sometimes, you just need your music to make you a goddamn space marine.

Sunday, December 2, 2012

Go read this

File under, "I really wish I had written this:" Katherine Cross's "Game Changer."

Cross does her homework and her research, and articulates very clearly and cleanly the theories that I--and anyone else who examines sexism in gaming--have bandied about for ages. She even looks at the moving goalposts: if women like it, it is no longer a "real game."

It is hardly surprising that some men perceive the gaming world as, in Kimmel’s words, a “virtual men’s locker room” threatened by the presence of women. When women inhabit this space, claim visibility, and attempt to shape it, their presence becomes an existential threat to that “not PC” safe space that some of these young men enjoy. When abuse occurs, the conceit is that it’s “just a game,” which enables people to—in the words of one of Kimmel’s interviewees—“offend everyone!” It’s not like real life, which is too, well, real to risk flagrantly violating norms of decorum. But, at the same time, these male gamers know that the space is a real, tangible thing, in need of protection. Their “offending” serves to police the boundaries of who can and cannot inhabit gaming culture, and to keep out people who threaten “their” space.

Cross does her homework and her research, and articulates very clearly and cleanly the theories that I--and anyone else who examines sexism in gaming--have bandied about for ages. She even looks at the moving goalposts: if women like it, it is no longer a "real game."

Thursday, November 29, 2012

What It's Like Inside My Brain

Last night, we were playing Red Dead Redemption. I had successfully steered the ponypony somewhere and M was shooting some guys. They probably deserved it. I made some offhand comment about the game.

"Well, it is a Western," he replied.

"Maybe in a sense, all games are kind of Westerns," I mused.

"There's an article," he quipped back.

***

If my thought process resembles anything, it's probably the Molydeux Twitter account. I tilt my brain and stuff falls out. Sometimes it's awesome. Sometimes it's not. When it manages to connect to something else that's rattling around in there, it's an article.

***

"The word 'yellow' wandered through his mind in search of something to connect with. Fifteen seconds later he was out of the house and lying in front of a big yellow bulldozer that was advancing up his garden path."

***

I'm not quite sure why I thought that all games were Westerns, but if I sat back to argue it, I bet I'd come up with a connection. Something about the lone hero, probably, but then that would have me delving back into my film history books to define why the hero of the Western was the way he was.

***

In my self-image and self-perception, I still suck at consoles. Despite having played a huge number of games on the PS3 this year for review and for fun. Why was I so surprised that steering the ponypony around the not-entirely-wild-but-wild-enough-West of the turn of the last century wasn't hard for me? After dozens or hundreds of hours of PS3 time, why am I still surprised at myself for, yes, knowing how to use the blasted machine?

***

When I came back to the blog this week, I discovered twenty-three (23!) abandoned drafts and half-drafts from over the years. Some had their best paragraphs lifted and folded into other things; others just sit, as husks, with their careless author having long since forgotten why they were important to begin with.

***

There are notes on the whiteboard on my wall, on post-its all over my desk, jotted into the little notebook I keep tucked inside my purse. "Kinect - class - space - McMansion - who games for" is one that makes sense. I can remember that. And it's written down twice, which means I thought it was important at least twice.

***

Maybe "Beyond the Girl Gamer" would be a good title for a weekly column, somewhere, that addresses topical gender issues in gaming.

***

I have a note that says "JUST LIKE Dark Souls," a game I have never, in fact, actually played.

***

This is the truest comic I have ever read. Among many true comics.

***

I've got three separate notes on the nature of online multiplayer as the 21st century continues to unfold, two on Sherlock Holmes (the 2009 movie), and one full angry screed about over-reliance on the Cold War that, somwhere in the middle, morphed into a meditation on how the maturity of game narratives is attached to the maturity of the cinema it chose, unnecessarily, to ape.

That one about how combat is and isn't a useful mechanism for storytelling--that's one I keep promising myself to write. I know a dozen other folks already have. Someday, I'll have to do it anyway.

***

Today, I feel like I am out of ideas. I am dwarfed, overawed, by the incredible things my colleagues and peers--my friends--have written.

I hate those people.

I love those people.

***

The thing is, if I wrote that column, I'd become, even more than I am, that "girl" writer. Not that game writer. Or that writer.

***

Until Tuesday night, I had the Omega review to hang onto. I played it. I wrote about it. And then it was done. Two days, two measly days, without the anchor and already I am asking the cat if Communism really was just a red herring, and why Gandhi is always such an asshole in Civ games.

***

Everyone's wished me luck, asked where I'm going next. I'm not being coy or teasing when I say that even I don't know; I really don't know. Aside from trying to convince the Commonwealth of Virginia that they are the ones who owe me unemployment, and that they can't fob me off on New York or Maryland, I really don't know what I'll be doing next week.

***

I'll be vacuuming my apartment like mad. Twice. Each day. My cat-allergic parents are coming to town the week after.

***

I want my friends and colleagues and peers to be wildly successful, famous, rewarded with piles of cash.

I want to pay my rent.

I really hate competitive games.

***

I really, really want a Coke. Or maybe a beer. Maybe I can learn to like beer.

Maybe I can learn to like a lot of things.

I'd learned to like Kotaku. A lot. Really a lot.

***

I always said I hated BioWare-style RPGs and then 2010 and 2011 and 2012 and Mass Effect 3 and Dragon Age 2 came and went and now even the people who make those games have publicly noticed my rather excessive love for them. I still have a paycheck, for another week. Time to get the Baldur's Gate Enhanced Edition and teach myself some history.

Then I can write about the experience.

That's an article.

"Well, it is a Western," he replied.

"Maybe in a sense, all games are kind of Westerns," I mused.

"There's an article," he quipped back.

***

If my thought process resembles anything, it's probably the Molydeux Twitter account. I tilt my brain and stuff falls out. Sometimes it's awesome. Sometimes it's not. When it manages to connect to something else that's rattling around in there, it's an article.

***

"The word 'yellow' wandered through his mind in search of something to connect with. Fifteen seconds later he was out of the house and lying in front of a big yellow bulldozer that was advancing up his garden path."

***

I'm not quite sure why I thought that all games were Westerns, but if I sat back to argue it, I bet I'd come up with a connection. Something about the lone hero, probably, but then that would have me delving back into my film history books to define why the hero of the Western was the way he was.

***

In my self-image and self-perception, I still suck at consoles. Despite having played a huge number of games on the PS3 this year for review and for fun. Why was I so surprised that steering the ponypony around the not-entirely-wild-but-wild-enough-West of the turn of the last century wasn't hard for me? After dozens or hundreds of hours of PS3 time, why am I still surprised at myself for, yes, knowing how to use the blasted machine?

***

When I came back to the blog this week, I discovered twenty-three (23!) abandoned drafts and half-drafts from over the years. Some had their best paragraphs lifted and folded into other things; others just sit, as husks, with their careless author having long since forgotten why they were important to begin with.

***

There are notes on the whiteboard on my wall, on post-its all over my desk, jotted into the little notebook I keep tucked inside my purse. "Kinect - class - space - McMansion - who games for" is one that makes sense. I can remember that. And it's written down twice, which means I thought it was important at least twice.

***

Maybe "Beyond the Girl Gamer" would be a good title for a weekly column, somewhere, that addresses topical gender issues in gaming.

***

I have a note that says "JUST LIKE Dark Souls," a game I have never, in fact, actually played.

***

This is the truest comic I have ever read. Among many true comics.

***

I've got three separate notes on the nature of online multiplayer as the 21st century continues to unfold, two on Sherlock Holmes (the 2009 movie), and one full angry screed about over-reliance on the Cold War that, somwhere in the middle, morphed into a meditation on how the maturity of game narratives is attached to the maturity of the cinema it chose, unnecessarily, to ape.

That one about how combat is and isn't a useful mechanism for storytelling--that's one I keep promising myself to write. I know a dozen other folks already have. Someday, I'll have to do it anyway.

***

Today, I feel like I am out of ideas. I am dwarfed, overawed, by the incredible things my colleagues and peers--my friends--have written.

I hate those people.

I love those people.

***

The thing is, if I wrote that column, I'd become, even more than I am, that "girl" writer. Not that game writer. Or that writer.

***

Until Tuesday night, I had the Omega review to hang onto. I played it. I wrote about it. And then it was done. Two days, two measly days, without the anchor and already I am asking the cat if Communism really was just a red herring, and why Gandhi is always such an asshole in Civ games.

***

Everyone's wished me luck, asked where I'm going next. I'm not being coy or teasing when I say that even I don't know; I really don't know. Aside from trying to convince the Commonwealth of Virginia that they are the ones who owe me unemployment, and that they can't fob me off on New York or Maryland, I really don't know what I'll be doing next week.

***

I'll be vacuuming my apartment like mad. Twice. Each day. My cat-allergic parents are coming to town the week after.

***

I want my friends and colleagues and peers to be wildly successful, famous, rewarded with piles of cash.

I want to pay my rent.

I really hate competitive games.

***

I really, really want a Coke. Or maybe a beer. Maybe I can learn to like beer.

Maybe I can learn to like a lot of things.

I'd learned to like Kotaku. A lot. Really a lot.

***

I always said I hated BioWare-style RPGs and then 2010 and 2011 and 2012 and Mass Effect 3 and Dragon Age 2 came and went and now even the people who make those games have publicly noticed my rather excessive love for them. I still have a paycheck, for another week. Time to get the Baldur's Gate Enhanced Edition and teach myself some history.

Then I can write about the experience.

That's an article.

Tuesday, November 27, 2012

Oh, my, it's quite dusty in here...

Oh, hello. *blows the dust off the blog* I, er, let things sit around here for rather a long time, didn't I.

So, I said back in February that I was going to try to do a monthly best-of link roundup to my work from Kotaku. That promise very clearly fell by the wayside, and hard. Sorry about that. I just ran out of steam, most weeks. But better late than never, right?

Anyway, a roundup is easier when you know where it ends. It has been a privilege and a pleasure working with the team at Kotaku. It certainly made 2012 interesting in a number of unexpected ways. That particular adventure, though, has drawn to a conclusion; the site and I officially part ways on December 1. It's time for a new adventure.

Meanwhile, I've got a veritable mountain of links after the jump. It's not everything I posted at the site (most weekdays, I ran between 3 and 8 stories); just the ones I can remember as a best-of. Criticism, impressions, and general essays are arranged by month, with all the full game reviews (all of 'em) afterward in alphabetical order. Because I am nothing if not compulsively organized.

So, I said back in February that I was going to try to do a monthly best-of link roundup to my work from Kotaku. That promise very clearly fell by the wayside, and hard. Sorry about that. I just ran out of steam, most weeks. But better late than never, right?

Anyway, a roundup is easier when you know where it ends. It has been a privilege and a pleasure working with the team at Kotaku. It certainly made 2012 interesting in a number of unexpected ways. That particular adventure, though, has drawn to a conclusion; the site and I officially part ways on December 1. It's time for a new adventure.

Meanwhile, I've got a veritable mountain of links after the jump. It's not everything I posted at the site (most weekdays, I ran between 3 and 8 stories); just the ones I can remember as a best-of. Criticism, impressions, and general essays are arranged by month, with all the full game reviews (all of 'em) afterward in alphabetical order. Because I am nothing if not compulsively organized.

Wednesday, May 30, 2012

"So what's it like...?"

In the past just-over-three months, many friends and acquaintances have all asked me the same question:

"So what's it like, working at Kotaku?"

In terms of the day-to-day details, my colleague Kirk Hamilton's look at a week in the life is, while obviously different in the details, pretty similar in the big picture.

Friday, March 23, 2012

Mass Effect 3 and Me

I've written a lot about Mass Effect 3 in the last few weeks. Suffice it to say, I'm a fan of the game and don't feel the slightest bit "betrayed" by it, though I do think some (not all) of the concerns many players have with the endings are indeed valid criticism, and I understand deeply why there's so much emotion tied up in the criticism as well.

Here's a brief round-up of the interesting things I've had to say about the game so far:

Review: based on a very fast, default-Shep playthrough; it had to be ready to go into the world at midnight on launch day. And it was still a great game.

I also got to make a cool gallery of some of the voice actors, and my co-worker Chris made a video I love out of the screenshots I took from my Shep's game (contains spoilers).

And then there's the piece I'm most glad I wrote (spoilers, obvs), Why Mass Effect 3's Ending Doesn't Need Changing. And if I'm being strictly honest (eeeeeeeeeeeeee) this tweet about that piece, from a certain Jennifer Hale, made my week.

(Edited March 24 to add Dan Bruno article link.)

EDIT Afternoon March 24: I have deleted all comments and locked the post. The discussion, such as it was, was circular, uncivil, and unproductive. For readers wishing to discuss the merits of the game itself, see previous ME3 post.

Friday, March 9, 2012

It's Mass Effect 3, People!

You want to talk about Mass Effect 3. I want to talk about Mass Effect 3. We all want to talk about Mass Effect 3.

Romances! Characters! Dramatic moments! Sad things! Funny things! Happy things! Decisions! Locations! It's all in our heads a-buzzing.

So here is a place where we can all talk in more than 140 characters. THERE WILL BE SPOILERS IN THE COMMENTS. However, you can collapse comment threads on Disqus. So I ask that if you are writing about the very, very final act of the game, you say so in a comment and then reply to yourself with your spoilers, so that folks who want to talk mid-game but not blow the ending can still scroll on by.

Have at it!

Romances! Characters! Dramatic moments! Sad things! Funny things! Happy things! Decisions! Locations! It's all in our heads a-buzzing.

So here is a place where we can all talk in more than 140 characters. THERE WILL BE SPOILERS IN THE COMMENTS. However, you can collapse comment threads on Disqus. So I ask that if you are writing about the very, very final act of the game, you say so in a comment and then reply to yourself with your spoilers, so that folks who want to talk mid-game but not blow the ending can still scroll on by.

Have at it!

Thursday, February 2, 2012

Major Blog News, 2012 Edition

First, the sad news: Updates here at the blog are about to become infrequent at best.

Now, the good news: It's because your critic did, indeed, find another castle. Beginning Monday (February 6), I will be joining the staff of Kotaku as a full-time writer. Rather than seeing me try to cobble together several updates per month around my day job, you are going to see me try to cobble together several updates per day as my day job.

I am thrilled with this opportunity. It's an amazing chance to broaden my own skillset and audience, and with the time to research and write and the resources to expand my reach I hope to be able to investigate many ideas I would not have been able to before. Likewise, I am one of several new staff who will be continuing to expand Kotaku's voice beyond where it traditionally has been.

I owe huge thanks to everyone who has been reading and linking my work over the last two years, and in particular, to those who have consistently championed this blog and my writing to the wider world, and who have been welcoming mentors. In no particular order, I'd like to thank Alyssa Rosenberg, Alli Thrasher, Lesley Kinzel, Amanda Cosmos, Dennis Scimeca, Kris Ligman, Chris Dahlen, Emily Hauser, the entire staff of The Border House, everyone at Critical Distance, TNC's Horde, and of course my new boss Stephen Totilo, for offering me this new opportunity.

And last but most emphatically not least, I extend my sincere gratitude to all of my friends and family who have put up with my madness and passion (particularly my poor husband), and who always encouraged me to keep writing (particularly my parents). The several dozen of you who I talk with daily on Twitter and G+, among other venues, give me constant inspiration and keep me on my toes. Never stop: I'm going to need all of the discussion, inspiration, and encouragement I can get from here on out!

I will still be posting occasionally, when I have something to say that's not really appropriate for the new digs. I also plan to stick weekly or monthly "best of" link roundups to my Kotaku pieces over here. So the blog's not dead... just evolving. :)

[ETA: Also HOLY SHIT thank you all for the immense outpouring of support and congratulations here, on Twitter, and in e-mail or over at TNC's. It's incredibly appreciated, thank you. <3 ]

Wednesday, February 1, 2012

Guest Post: Finding Middle Ground

After I shot off The Golden Days in December, Dennis Scimeca, the friend whose tweet I quoted, asked for an opportunity to present his point of view more clearly, in more than 140 characters. He sent me the first draft of this post early this week, and after we talked about it I agreed to run it.

Dennis is a friend with whom I have often disagreed but I enjoy having discussions with him, and I think every argument we have clarifies the way both of us think (in a good way). I hope you, my readers, will afford him the same careful listening and respect you so regularly afford to me.

-----------------------------------------------------

Finding Middle Spaces

Dennis Scimeca

Kate has been gracious enough to allow me to continue a

conversation in the same space in which it began, to wit Kate’s post “The Golden Days.”

It turns out, according to my esteemed host that the referenced comment I made

on Twitter was the inspiration for that post, which I’ve continued to find

upsetting because I still haven’t clearly made the point ensconced in that

statement, a point which I don’t think will be found offensive by most.

First, I want to apologize having potentially derailed a

conversation about gender assumptions in gaming. I’d denied being derailing in

my response to “The Golden Days” because I was laboring under the

misunderstanding that derailment has to be an intentional act. It doesn’t. Lesson learned and accepted!

|

| When I was a kid, “diversity” would have meant “boys + girls,” which I guess explains how I conceived of the metaphor below. |

I’ve been struggling to come up with an explanation by which

to make plain the intended meaning of

that statement, and the best I’ve come up with has been the metaphor of a

schoolyard. I’m standing in the schoolyard with a bunch of my friends from

middle school, all boys, and we’re passing around a game manual. We’re talking

excitedly about how awesome it is, and how hard it was to beat that boss on the

seventh level, and what our strategies were for beating that boss.

I look across the schoolyard and see a group of girls

passing around the same game manual. I

wander over to them in the hopes of joining their conversation. It’s definitely

the same game manual, but a very

different conversation. They’re asking why they can only play the game as a boy

character. And why are all the boobs on all the girl characters so huge? And

why are all the girl characters so inept in the story, while all the boy

characters are heroes?

This group of girls is angry, and frustrated, but all their

points are valid and I find them extremely interesting. But I also wonder

whether or not they found it hard to beat that boss on the seventh level, and

what their strategies were for beating that boss. It wouldn’t be polite for me

to just introduce that totally different topic in the middle of that other

conversation, and the best I can do is observe the problems they’re noting and

nod in agreement, but I don’t really have anything to add because these aren’t my issues, so I fade away from their

group.

Now I’m standing in the middle of the schoolyard alone. I

don’t want to go back to that group of boys over there because their conversation

seems kind of boring now, and I can’t go back to that group of girls over there

because they’re having a conversation I can’t really participate it actively. What

I’d really like, instead of seeing these two segregated groups, is to get

everybody together and talk about that boss on the seventh level because it

would be in the midst of that conversation that we were all just a bunch of people who play video games.

If there is such a thing as “gamer culture” it is centered around and originates from the activity of playing video games, and the base set of experiences that everyone who plays video games shares. That is the shared cultural heritage. Not the reactions to, but the doing of. No matter how we react to the subject matter in a given video game, we all shared the experience of playing it.

|

| In this immediate space, everyone is “just a gamer.” |

If there is such a thing as “gamer culture” it is centered around and originates from the activity of playing video games, and the base set of experiences that everyone who plays video games shares. That is the shared cultural heritage. Not the reactions to, but the doing of. No matter how we react to the subject matter in a given video game, we all shared the experience of playing it.

When I read Mattie Brice’s guest editorial “Why I Don’t

Feel Welcome at Kotaku,” I heard someone who wanted into a cultural space from

which she felt isolated. The assumption is that “gamer culture” is dominated by

cis-gendered white men who don’t want anyone else in their space, and who are

hostile to women or homosexuals or transgender people who want into that space.

And I think it’s time to question whether or not that is a description of

“gamer culture” or a certain, admittedly large portion of gamer culture which

is still holding on to the old way of things, but which is no longer an

adequate descriptor for the totality of gamer culture. In other words, Mattie

might feel that Kotaku is “for heterosexual white American men gamers,” but

it’s probably unhealthy to assume that Kotaku represents “gamer culture” writ

large. Kotaku represents Kotaku.

People who take video games to task for their problematic

presentations of gender or sexual preference and all the rest do so because

they love video games. They have to discuss those issues because nothing

changes if they don’t, and we have spaces for those discussions. They’re

difficult and troublesome and the fact of the matter is not everyone is

equipped with the skills or the emotional strength to handle them. As Border

House editors have told me, those conversations are exhausting. Don’t we also

need spaces which aren’t focused on those exhausting and potentially-alienating

discussions to define a new normative, a new “baseline” space within which

people just talk about video games?

I’m waiting for a new sort of space that is decidedly

enthusiast-facing, which celebrates the raw experience of playing of video

games, but with an audience that

represents the actual, accurate face of the game playing audience. And I’m

not just referring to acknowledgment of the approximate 60/40 male/female

gender split among the gaming population or inclusion of marginalized groups,

but acknowledgement of the ridiculousness of all the traditional divisions like

“hardcore” and “casual,” or PC/console vs. social/mobile.

I’m waiting for a space where playing games

is about playing games but for everyone, where people who are in that space look

around them and see diversity of identities and interests and technologies,

because that’s the space which will create the new paradigm of what it means to

be a “gamer.”

Kate says that this new “golden age” will only arrive when we’re part of “a

society that's come to terms with understanding sex, gender, race, and a whole

lot more.” It’s going to be a long, long time, maybe never, before we reach

that goal and if that’s the precondition we set for ourselves to create the

kind of space I’m longing for, it may never happen. So why can’t we, in

addition to having all of these dedicated spaces for calling out the legitimate

issues that need addressing, also start building our new enthusiast spaces now?

I’m waiting for that middle space on the playground where

everyone’s all thrown together and they’re passing around that game manual and

telling the tales of how fucking hard that boss was on the seventh level, and

figuring out the best way to beat it, and laughing about the stupid mistakes

they made and that glitch they found over in the corner of the boss’s lair

where they phased through the floor and got stuck. Creating that space is just as important a part of the struggle as

addressing the issues that necessitate the struggle in the first place.

I am, again, coming at this entire conversation from a

perspective of privilege. I see these issues because I make myself look at

them, not because I live them, and I’m cognizant of that. But I want to make it

clear that I’m not asking people to just “come over to my side of the culture,”

and “just talk about video games and forget the rest.” I’m saying that I’m

continuing to walk away from what “my side” of the video game culture was, but

right now I don’t have another destination to arrive at.

I do miss the times when playing video games was just about

playing video games, and the only way I can return to that place right now is

by turning my back on all the issues whose recognition has spoiled my innocence

and wallowing in my privilege, which I’m not willing to do. I mourn the loss of those innocent days while at the same

time recognizing that if those days were born at the expense of someone else’s

pain or exclusion, good riddance.

Monday, January 9, 2012

The Age of the Dragons, part II: The Tragedie of Kirkwalle

Two households, both alike in dignity,

In fair Verona, where we lay our scene,

From ancient grudge break to new mutiny,

Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean.

From forth the fatal loins of these two foes

A pair of star-cross'd lovers take their life;

Whole misadventured piteous overthrows

Do with their death bury their parents' strife.

In my 9th grade English class, we read Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet.

Nearly every public school freshman class in the United States does

this, still, and has done for decades. It's an educational rite of

passage: turn 14, read about two horny Elizabethan teenagers and how

they died.

At the time, I hated reading Romeo and Juliet. I resented everything about it and only began to change my mind when Shakespeare in Love was released a few years later. With the full force of ironic detachment that only a teenager can muster, I knew that it was "stupid."

At the time, I hated reading Romeo and Juliet. I resented everything about it and only began to change my mind when Shakespeare in Love was released a few years later. With the full force of ironic detachment that only a teenager can muster, I knew that it was "stupid."

But my English teacher was a wise woman.* I remember very little of the details of her class, half a lifetime later, but I remember her teaching the prologue. The tension, she explained, came from knowing that the story would end badly. The core of the tragedy was in the audience understanding as the play unfolded that disaster could be averted, but having foreknowledge that it wouldn't be. The story, from the outset, was a tale of doom, and in that knowledge lay its art and its power.

Romeo and Juliet and I eventually came to a truce, and while it's still not among my favorites, I respect it for what it is. But in 10th grade English, a scant few months later, I took to Macbeth immediately and have remained a fan of the art of the Tragedy ever since.

The typical model of a video game -- and particularly, a BioWare video game -- is to collect your allies, fight your enemies, and save the world. These stories might have nuance in the details, but ultimately their shape is unambiguous and Romantic. They're all variations on the hero's journey, and the player character is front and center to the story. He or she is the lynchpin of all that happens in the game world, and his or her actions and skills can guarantee a positive outcome for The Good Guys.

Players went in to Dragon Age 2 expecting the arc of Star Wars and instead got handed something out of Sophocles. Saving the world, after all, is par for the course. No wonder so many were disappointed with what they got.

"I'm not interested in stories. I came to hear the truth.""What makes you think I know the truth?""Don't lie to me! You knew her even before she became the Champion!""Even if I did, I don't know where she is now.""Do you have any idea what's at stake here?""Let me guess: your precious Chantry's fallen to pieces and put the entire world on the brink of war. And you need the one person who could help you put it back together.""The Champion was at the heart of it when it all began. If you can't point me to her, tell me everything you know.""You aren't worried I'll just make it up as I go?""Not. At. All.""Then you'll need to hear the whole story..."

The events in Kirkwall leading up to the beginning of the Mage-Templar war centered around Carias Hawke. She was quick with her wit and quicker with her daggers. She was ruddier than her dark-haired sister Bethany, but anyone could tell they were sisters at a glance. She tried to help apostate mages like her sister as best she could. With all of her family lost to her, over time, she found unexpected comfort and love in the arms of a fugitive warrior elf from the Tevinter Imperium. Although she knew him for seven years, she never did really understand what drove Anders -- once a close friend -- to recklessness, madness, and disaster. Despite being deeply betrayed, she could not make herself betray in turn and so she chose to let Anders live, sending him away with the unspoken promise of a knife between the ribs if he should ever dare to show his face again.

The events in Kirkwall leading up to the beginning of the Mage-Templar war centered around Owen Hawke. He was even-tempered, if prone to sarcasm, and though he was always willing to use his magical talents he, like his late sister, spent a lifetime carefully (if ultimately unsuccessfully) avoiding Templar attention. In looks, he favored his brother Carver. With all of his family lost to him, over time, he found his way into a torrid, passionate relationship with a fellow apostate and runaway Grey Warden. He always knew what danger lurked within Anders but felt that maybe, if he didn't poke at it, they could avoid recklessness, madness, and disaster. Despite a zealous, selfish, and destructive betrayal, he wouldn't turn on the man he loved. With no small measure of worry, he chose -- for a while -- to accept his lover's apparently sincere desire to remain in his life, and after the fight at the Gallows they disappeared into the wilds together.

The modern BioWare RPGs are, in a critical way, always about your story. The initial approach to one is the story the player has chosen to tell, for whatever reason: moral self-insertion; a pre-written, pre-determined RP approach to a character; the fine art of just picking things in the moment because you don't give a damn. It's an individual story, and the first playthrough becomes the story that the player tells about the events of the game. (This is true of both the Mass Effect and Dragon Age franchises, to date.)

The first story is my story. Carias (which sounds better than it's spelled) Hawke is my canon Hawke, and when Dragon Age 3 inevitably rolls around the events of her life are the tale I will import and carry forward. Hers is the story I have chosen to tell, and the game supported and encouraged my telling it.

The first story is my story. Carias (which sounds better than it's spelled) Hawke is my canon Hawke, and when Dragon Age 3 inevitably rolls around the events of her life are the tale I will import and carry forward. Hers is the story I have chosen to tell, and the game supported and encouraged my telling it.

The second story feels closer to being the story. Owen, through his outsider status as a mage and his relationship with Anders, uncovered huge swaths of motivation, narrative, and foreshadowing to which Carias was not privy. His was the second story I chose to tell, and the game not only supported and encouraged my telling it, but embraced it.

The key to reconciling these two different stories -- full arrays of different choices -- against each other and the fixed nature of the plot is through the mechanic of after-the-fact narration. It's interesting, seeing where the "Eye of God" viewpoint falls in Dragon Age 2. The story the player chooses to tell always meets some of the same goalposts, and while Varric's narration of events has a few tweaks, it's fundamentally immutable.

Indeed, for all that the player controls Hawke, in a meaningful sense the player is better represented by Varric. His presence as narrator -- and a potentially unreliable one, as far as both Cassandra and the player are concerned -- echoes and underlines the entire concept of the player making choices in what is ultimately a forced linear tragic narrative. "Here's how it really happened," the player says, and no one can particularly gainsay it because the ultimate sequence of events is still the same: Hawke came to Kirkwall in 9:30, in some way knew these 7 or 8 individuals, and in 9:37 was present when Anders destroyed the Chantry. Cassandra may stop Varric in moments of true absurdity but otherwise, she believes the story he has to tell about Hawke, no matter how it unfolds.

A brief diversion: one theory of visual arts (in particular, film) holds that the viewer's participation is a necessary part of creating meaning, including narrative meaning. The director and team who assemble a movie can give visual and aural depictions to their hearts' content, but true meaning comes from the viewer's foreknowledge and ability to make connections. For example, a shot in which the camera pans through a poor, downtrodden city neighborhood relies on the viewer's knowledge of urban poverty, or at least common cultural symbols of urban poverty, in order to work. Viewers with different backgrounds will create sightly different interpretations of such a shot and the film of which it is a part.

In the game, the player's participation in creation of meaning is more concrete, but in the same vein. Essentially, we at the keyboard or holding the controller are standing in the wings, feeding Varric his lines for Cassandra. The narrative on-screen is fixed: Hawke will always find the Thaig in the Deep Roads, Quentin will always kill Leandra, and Anders will always explode the Chantry. But much of the why is up to the player's interpretation and manipulation of the text.

|

| "A last toast, then: to the fallen." |

The stories of both Carias and Owen Hawke are arguably tragedies, in the classic sense. Only one of them gives all of the necessary markers along the way such that the player can see the shape of the story, understand its tragic nature, spot the oncoming disaster before it comes, and realize that Hawke in fact is not the center of the bigger tale.

The game more or less works no matter how one chooses to assemble its pieces. Any combination of friendship and rivalry, any combination of party members taken adventuring, and any Hawke class or set of skills -- all will add up to a total story. The player takes control of this Fereldan refugee and fills in the blanks however s/he likes, and it flows.

But rather than punishing the player for not making the "right" choices, Dragon Age 2 uses something of a carrot rather than a stick approach to authorial intent. The game rewards certain choices by adding layers of character background and motivation to certain stories and certain party combinations. My Hawke never knew that eventually, Fenris and Isabela could start a relationship -- and my other Hawke only found out by chance. My Hawke missed out on some of Anders's political passion, but my other Hawke found his lover's manifestos lying all over the house during the years they lived together in Hightown. My Hawke relied on Fenris to help her negotiate tricky moments with the Qunari; my other Hawke convinced Isabela to give the tome back.

I didn't feel shortchanged, at all, the first time I played through the game. (Or the second, which immediately echoed the first, with nearly identical choices but with a better understanding of how it all worked and eye to foreshadowing. Owen's game was number three.) I never regretted the decision to roll a female character, to play a class other than mage, or to avoid the Anders romance. I like that story, and that Hawke, and stand by the impulse to make it "my" canon. But that "other" Hawke -- the mage who had to deal with Carver, who lost Bethany, who chose Anders -- seemed to get the full story, in the shape of so much dialogue I might never have known was in the game. And while the game never forces a single direction on the player's character, when playing the "real" canon story, the "right" story, there's a feeling to be had that one has fallen very smoothly into the story that the game wants to tell.**

| |

| "There's power in stories, though. That's all history is: the best tales. The ones that last. Might as well be mine." |

The fun part is, no player would ever be able to discover the difference -- to hear all of the details of the story -- without playing through the game at least twice. Usually when we say a game has "replay value," we aren't talking about the strictly scripted, generally linear, straight-narrative games. After all: their skills are easy to master and we know how their stories go. Why revisit?

To me, the reasons to revisit Dragon Age 2 (beyond the same "old friend" reasons I revisit favorite books and movies) seem obvious: because this time, your concept of context is well enough honed to hear the prologue. Varric's words can no longer slide through your consciousness and back out: when he describes the state of the Chantry and the Circles, when he intimates doom for Hawke's sibling on the Deep Roads, when he convinces Cassandra "if Hawke had only known..." In all of these moments, Varric, our narrator, is helping us create the tragic arc.

Foreshadowing, after all, is a particular kind of thrilling agony when the player (viewer, reader) does, in fact, know what's going to happen as the story unfolds.*** And sometimes, it's the core of the entire thing. And so we find ourselves winding back to Shakespeare and to Aristotle, back to stories that advertise up-front that there is no winning solution to be had.

|

| "I removed the chance of compromise, because there is no compromise." |

The true story of Dragon Age 2, especially when thought of as the middle chapter of a story that began with Dragon Age: Origins and Awakening, is the tragedy of Anders and the Chantry. Hawke is a lens for understanding the story, rather than an end unto him- or herself. Such a construction directly contradicts nearly everything players have been led to expect from 20-30 years' worth of tradition and history in the western RPG.

Subverting expectations and deliberately playing with tropes is tricky, and Dragon Age 2 paid a price for its efforts. Close to a year after its initial release, player and critic opinions still stare each other down from across a mile wide, love-it-or-hate-it canyon.

In the end, perhaps it doesn't matter. Dragon Age 2 was exactly the right game, but it seems to have landed in the wrong franchise, or at the wrong time, or with the wrong marketing. BioWare's official position as they unofficially talk about Dragon Age 3 seems to be that they're willing to be carried at least in part by the tide shouting that this tragedy was a misstep. The internet clamors for the combat-focused, exploration-driven, skill-and-inventory driven classic party-based RPG that Dragon Age: Origins was heir to. DA2 instead brought a city full of companions to life and mainly gave the player's avatar a reason to be a witness to the inevitable bubbling over of violence that began the Mage-Templar War.

That war could yet destroy Thedas, and so whatever avatar takes center stage in the final installment of the trilogy will, I'm sure, be out to save the world. No doubt he or she will briefly meet survivors of both the Fifth Blight and the Battle of Kirkwall. And I suspect that he or she will find Thedas to be salvageable, and so help create a brave new world.

And stepping forth upon a new and mysterious shore, with all the problems of the world untangled? That one's for the Comedies.

***

For further reading on the telling of tragedies in video games: Line Hollis, Four Types of Videogame Tragedy. And for excellent further reading on Hawke and the Heroine's Journey, see here, on Flutiebear's tumblr.

* Mrs. Lucy Myers, of Belmont High School. To whom I owe rather a lot, not least of which is thanks for putting up with 14-year-old me.

**The Mass Effect franchise does this even more strongly than the Dragon Age franchise does. Although Shepard can make a limited variety of choices along the way, particularly in the area of romance, certain decisions (Liara) have less friction against the rest of the text in ME / ME2 than others do.

***Leandra's cheerful, happy talk early in Act II of finding a suitor is pretty much yell-at-the-computer heartbreaking on a second go.

Monday, January 2, 2012

Happy New Year! Etc.

The last big project I worked on in 2011 has now come to fruition, and yours truly has just appeared in issue 4 of Ctrl+Alt+Defeat, available here. There are several excellent pieces in there from a number of friends and critics, so I recommend a read.

Also, Critical Distance did their annual retrospective of This Year in Video Game Blogging, and this here little blog received a very nice shout-out indeed. You'll find many must-read pieces by many of my favorite writers in that post.

Also, Critical Distance did their annual retrospective of This Year in Video Game Blogging, and this here little blog received a very nice shout-out indeed. You'll find many must-read pieces by many of my favorite writers in that post.

Meanwhile, here at Your Critic, I'm gearing up for a busy January, with a week of guest-posting elsewhere, a possible letter series, a couple of big pitches, and a long overdue blog redesign.

Also, for the record, my 2011 Games of the Year were Portal 2, Dragon Age 2, and Bastion, not necessarily in that order. I realize this is hardly revelatory. Look for an opus on DA2, when I can finally decide which part I want to write about most, in the coming weeks.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)